The origin of soft skills

In January 2017 Seth Godin published an article called “Let’s stop calling them soft skills”. The main thrust of his article was that these ‘soft skills’ were the key to success in leadership and perhaps even happiness in life. We shouldn’t be calling them ‘soft’ when they are hard to acquire skills.

Since then the ‘soft skills’ redefinition movement has picked up steam, and people are actively looking for more appropriate terms to call them.

This got me thinking. Who called them soft skills? Why did they do that and what were they trying to distinguish them from?

The articles I read online didn’t cover this origin story; instead, they focus on the negative connotations of the word ‘soft’. So I did some digging.

It turns out ‘soft skills’ can be traced back to the US Military between 1968 and 1972. The military had excelled at training troops on how to use machines to do their job. But they were noticing that a lot of what made a group of soldiers victorious was how the group was led. This bothered the military as they weren’t training for that. So they went about creating a method to capture how this knowledge was being acquired.

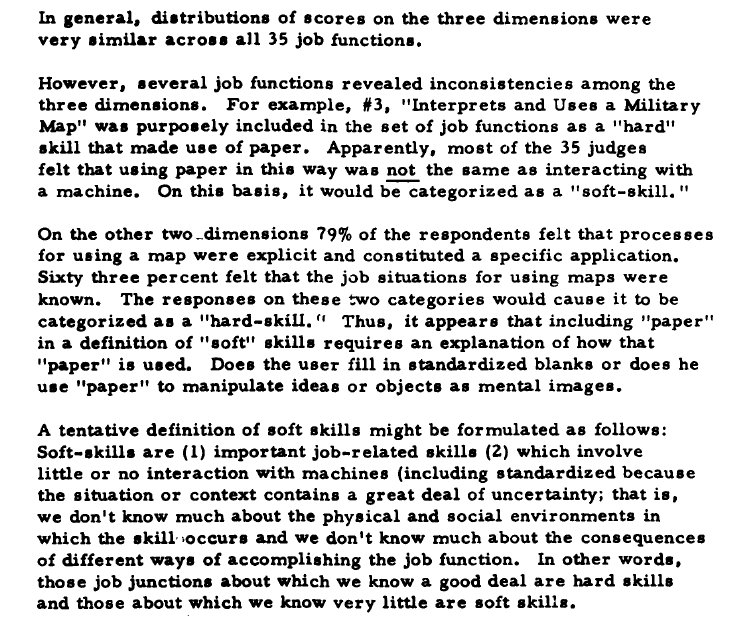

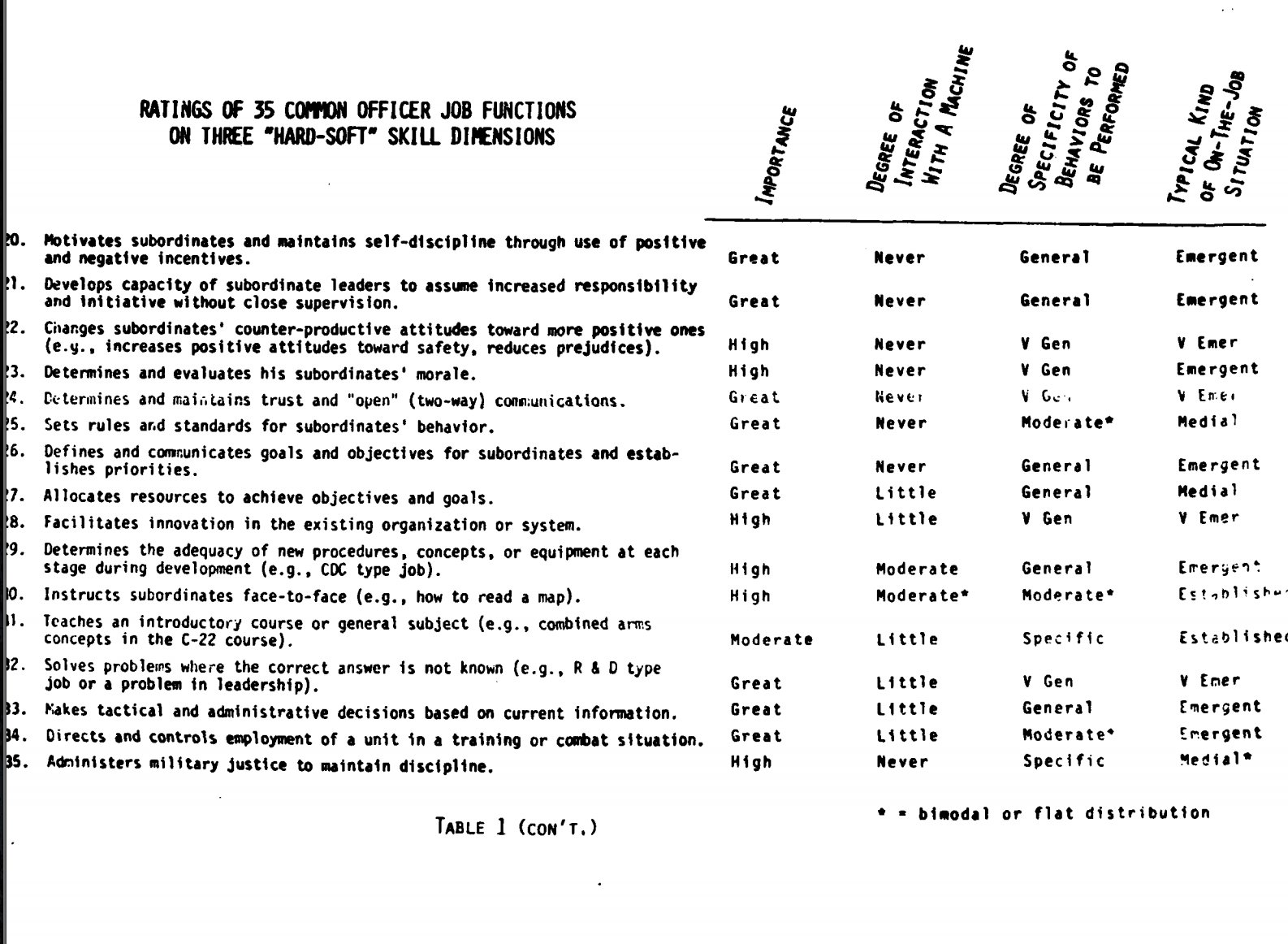

Paul G Whitmore is the name that comes up the most in these documents. His team came up with the contrast between working with something that is physically hard like a machine and anything else which is soft to the touch. From this research three criteria were created to judge if a skill is ‘soft’ or ‘hard’:

- Degree of interaction with a machine

- Degree of specificity of behaviour to be performed

- Typical kind of on the job situation

We’ll see some examples of these criteria in a moment.

The US military groups journey is now in the open as the documents have been declassified. Their conference in 1972 is a revealing read. A significant intellectual effort was dedicated to figuring out if map reading is a ‘soft’ or ‘hard’ skill:

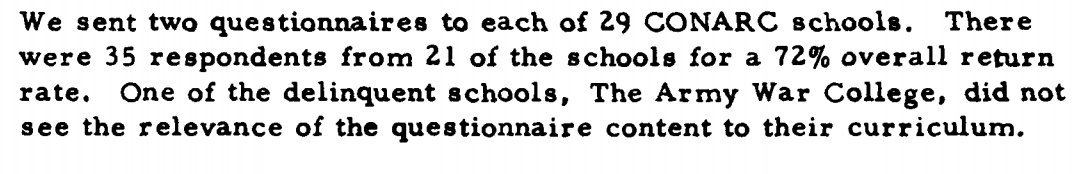

No expense was spared on this project. All of the military schools were creating controlled experiments and reporting back. Even IBM was involved. They built an 80 hole punch card machine that was designed to test soft skills.

However, the conference organisers were not too happy with how everyone responsed to their efforts:

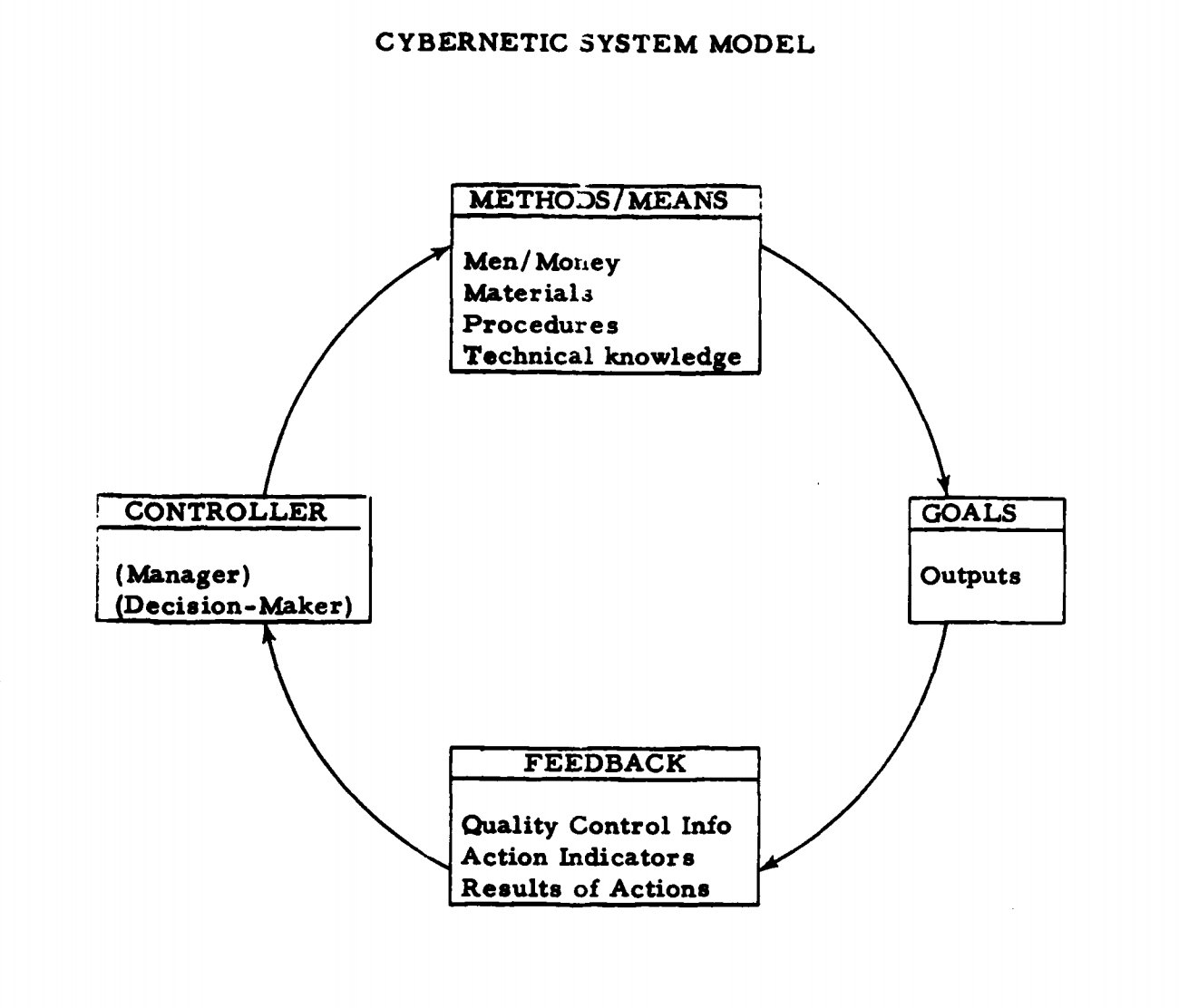

There was even a sort of Lean Startup object diagram involving Cybernetics:

Another large part of the conference was about the categorisation of skills and checking if the skill is emergent behaviour. The three ‘soft skill’ criteria took centre stage:

I recommend reading the whole document: http://www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a099612.pdf.

So we now know the US Military invented the term ‘soft skills’ to contrast with ‘hard skills’ that involved working with machines. But they weren’t trying to be derogatory towards these skills. They wanted to create a technological way of training and measuring how well their troops were performing. ‘Soft skills’ were taken seriously.

So let’s jump 46 years later to now.

Most people don’t know the history of the ‘soft skills’ term. We recognise that those skills are important, but the majority of training we do at school or work is technically focused. This frustrates those that recognise the untapped potential we have if we started teaching ‘soft skills’.

Should we rename ‘soft skills’?

The suggested alternatives are numerous, but the most common ones are ‘people skills’ and ‘EQ: emotional intelligence quotient’.

There are certainly problems with our cultural interpretation of the word ‘soft’. So I told my friend Marc Burgauer that I was going use ‘people skills’ instead. Marc replied with an insightful question:

“(is it) easier to reframe existing terms or change the terms?” – Marc Burgauer

Six months before Seth Godin’s piece the senior director at Jobs for the Future, Mary V.L. Wright pointed out the issue we have if we stick with ‘soft skills’

“If we’re not really good about defining what we mean by soft skills, it makes it very hard to teach them, and it makes them very hard to be sure your kids are doing well at them.” – Mary V.L. Wright

We’ve come full circle. From trying to make something hard to define easy to teach to having that same term used as a way to dissuade teaching it.

Let’s give it another 40 years.